Many of the weapons used in the murders of 119 journalists were imported – and Mexico’s laws and culture make tracing them impossible.– Phineas Rueckert from Forbidden Stories and Nina Lakhani

A collaboration with 24 international media outlets across 18 countries, and coordinated by Forbidden Stories, the Cartel Project investigates the global networks of Mexican drug cartels and their political connections around the world.

It was around daybreak when Mexican crime reporter Luis Vallejo received a call from a local police officer telling him that a bag of human remains had been found in the city of Salamanca where he lives.

Vallejo had become accustomed to calls like this: in recent years, violence in Guanajuato, the surrounding region, has spiraled to unprecedented levels amid bloody turf wars between rival cartels.

But when he reached the scene he found Israel Vázquez, a fellow reporter – and a lifelong friend of Vallejo – gasping for breath in a pool of blood. Vázquez, 31, had been shot 11 times by drive-by assailants as he prepared to broadcast live on Facebook. Police found bullet casings from two guns: a 9mm and a .45 caliber.

Vázquez, a father of two little girls, died later on 9 November, becoming the third journalist shot dead in 10 days in Mexico – the most dangerous country in the world for the media outside war zones.

“Everything came crashing down on me,” said Vallejo, 32, who was inspired to become a journalist by his friend.

A few days later, two men linked to the murder were arrested, along with seven other alleged local gang members. According to local news reports, authorities also seized an arsenal of high-caliber weapons from around the world, including a US-made semi-automatic rifle, Israeli and German assault rifles, and a modified semi-automatic shotgun from Turkey.

Since 2000, almost three-quarters of the 119 journalists murdered in Mexicowere killed by firearms, an investigation by the Cartel Project has found – and most of those weapons are imported.

“Almost all of the journalists in Mexico are killed with foreign weapons,” said Laura Angelina Borbolla, a former federal prosecutor in charge of investigating crimes against journalists. More than 90% of the killings remain unsolved.

An international coalition of journalists, coordinated by the non-profit Forbidden Stories, examined the flow of weapons into Mexico in an effort to understand where the guns are coming from.

The main findings include:

- Weapons manufactured in Europe and Israel sold legally to the Mexican army – as well as guns trafficked illegally across the US border – are probably being used to commit human rights violations and gangland executions, according to declassified military documents obtained by the non-governmental organization (NGO) Stop US Arms to Mexico.

- Trade is booming, but European arms companies are shipping hundreds of millions of dollars worth of guns, parts and ammunition to Mexican states with dire human rights records.

- Multinational arms companies could be violating European export laws as only a fraction of end-users are being reported, according to analysis of the documents published in a new report by a group of international NGOs.

- A combination of weak international regulations and a culture of impunity in Mexico makes tracing firearms used to commit crimes back to their origins virtually impossible.

A booming business

In 2006, the Mexican president, Felipe Calderón, launched a militarized war against drugs which has been continued by successive presidents, and has led to a sustained surge in human rights violations. Violence has since soared: about 300,000 people have been murdered, and tens of thousands more have disappeared.

Mexico’s misery has been a bonanza for the arms trade.

According to US International Trade Commission data, about 28,465 weapons, mostly handguns, were legally sold to Mexico in 2019, but many more US weapons are trafficked across the border, with some estimating as many as 213,000 weapons illegally making their way to Mexico each year.

And between 2006 and 2018, European and Israeli companies exported more than 238,000 firearms to Mexico for use by state and local police. More than half came from just two companies, Beretta, based in Italy, and Austria-based Glock, in trade deals worth tens of millions of euros, according to declassified Mexican military documents obtained by Stop US Arms to Mexico.

The documents show that European weapons have regularly been sold to states where security forces have a well-documented history of human rights violations and collusion with criminal groups, such as Guerrero, where local police and soldiers have been implicated in the 2014 forced disappearance of 43 trainee teachers.

“In most cases where we have documented enforced disappearance, there is always this collusion between the state authorities and organized crime – and there is always the exchange of weapons between these two entities,” said Erika Guevara Rosas, the Americas director for Amnesty International.

Beretta and Glock did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Even countries that sell relatively few weapons to Mexico – such as the United Kingdom – have seen exports increase. According to figures from Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT), UK export licenses to Mexico increased from 58 in 2008 to 350 in 2017.

In early 2015, just weeks after the 43 students were forcibly disappeared, the UK ambassador to Mexico told the Guardian: “In the long term we would aspire to become a player in Mexico’s military procurement.”

Since then, Mexico is listed as a “priority market” for arms exports for the UK.

While most licences have been for large-scale military equipment, the UK has also sanctioned £4m of small arms to Mexico. But the true value of the arms deals could be higher, as there were three open export licences which campaigners say make tracking sales much more difficult. Open export licences, which typically last for about five years, allow for unlimited exports.

“By using this opaque mechanism, the government is making proper scrutiny of arms sales even harder,” said Andrew Smith of CAAT.

A government spokesperson said: “The UK operates one of the most comprehensive export control regimes in the world.”

A perverse monopoly

In Mexico, the army controls all weapons imports and resales to local and state police, and private individuals. More than 95% of European weapons the army has sold to police forces since 2006 were classified as for “military use” under Mexican law, which on paper restricts legal gun sales to civilians.

Beyond the use of these arms by police, evidence suggests that some of the European weapons flooding the market in Mexico have also been linked to the killing of journalists, human rights defenders and civilians, according to analysis of the army documents published in a new report, by a group of international NGOs including Global Exchange.

José Armando Rodríguez Carreón who worked for El Diario de Ciudad Juárez, was shot dead in 2008 with an Italian pistol, according to prosecutor Borbolla. In 2013, a Belgian weapon was used to gun down Jaime Guadalupe González Domínguez in the northern state of Chihuahua.

Veracruz – the Mexican state with the highest number of journalists killed since 2000 – has regularly received weapons and ammunition from a number of European and Israeli companies.

US law enforcement officials said that the many killings and disappearances, including of local journalists, in Veracruz during the 2010-2016 administration of Governor Javier Duarte, could not have taken place without complicity between the cartels, politicians and police.

The most frequently targeted journalists are those who dare to investigate relationships between corrupt officials and organized crime. The Mexico Violence Resource Project estimates that nearly half of threats against journalists came from state actors such as police and mayors, compared to 5% by criminal groups.

Despite this, international weapons manufacturers are undiscerning when it comes to selling to states with a long track record of human rights violations, according to John Lindsay-Poland, the director of Stop US Arms to Mexico.

“They clearly know that weapons are going to states like Guerrero and Veracruz and Tamaulipas and Chihuahua that have long, well-documented histories of corruption and human rights abuses and impunity,” he said. “In our view, they’re culpable.”

Evidence suggests that significant numbers of military-grade European weapons have ended up in the hands of cartels, according to Forbidden Stories’ analysis of open-source photos.

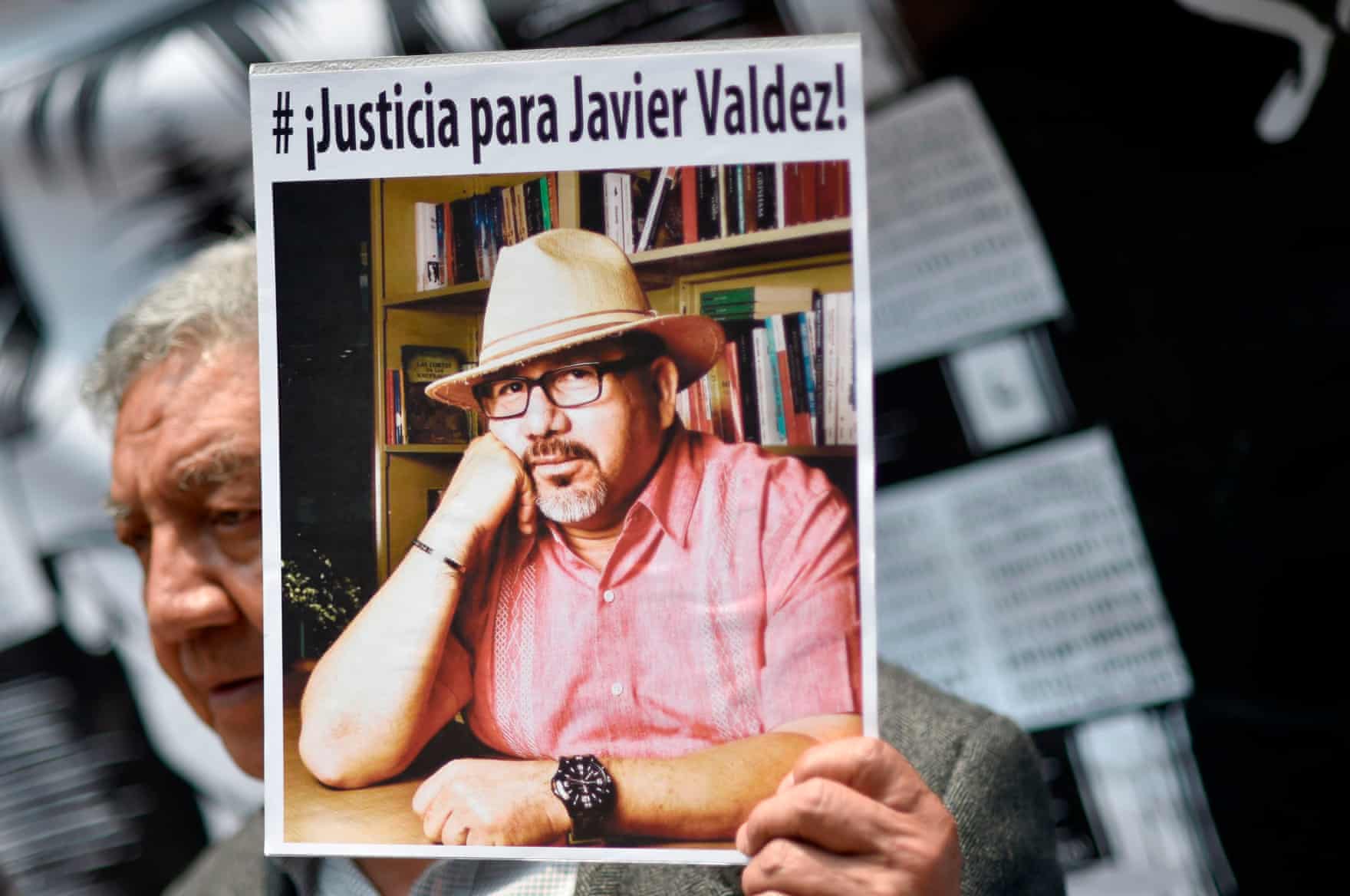

Security guards working for Dámaso López Serrano – the son of a senior lieutenant in the Sinaloa cartel, who Mexican prosecutors say ordered the murder of journalist Javier Valdez in 2017 – were photographed carrying a German-produced machine gun. The same model has been sold to police in more than half of Mexico’s 32 states including Sinaloa, according to the declassified documents.

Other cartels have also obtained military grade weaponry from abroad. Images from the attempted assassination of police chief Omar García in Mexico City in June 2020 by the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generacion show a Belgian assault rifle sitting in the bed of a pickup truck.

In the past decade, more than 4,000 weapons from companies based in Europe – Italy, Romania, Austria, Belgium and Germany – were recovered at crime scenes in Mexico, according to the army documents.

Between 2000 and 2015, more than 20,000 weapons were lost by or stolen from federal, state and local police, according to the army data. In Guerrero and Tamaulipas, two of the most violent states in Mexico, 20% and 10% of weapons respectively, were lost between 2006 and 2017.

After Israel Vázquez was shot dead in Salamanca, protesters took to the streets when the local mayor appeared to blame the journalist for reporting early in the morning in a dangerous neighborhood.

Despite the arrest of two men linked to his murder, Vázquez’s colleagues continue to demand a full investigation into the weapons and motive behind the killing.

“The people of Salamanca are demanding justice for Israel – for the loss that he left as a brother, son, father and friend,” Vallejo said. “We don’t want him to be just another cold case.”

Additional reporting by Veronica Espinosa (Proceso) in Guanajuato and Dana Priest (The Washington Post)

From the Guardian