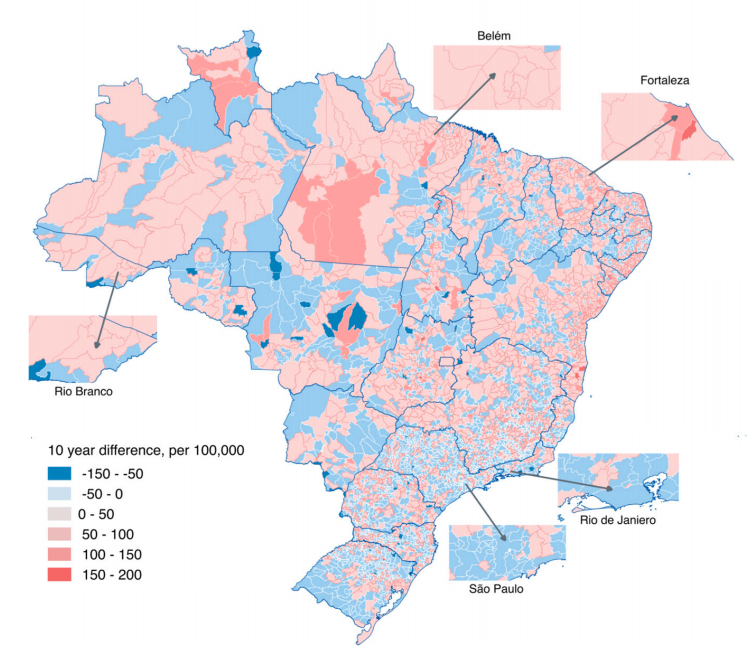

A new Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH) study maps changes in homicide rates across Brazil from 2000 through 2014. Published in the journal Injury Epidemiology, the research shows the success of anti-violence efforts in major urban areas such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Espirito Santo, but the explosion of homicides in fast-developing northeastern areas is a warning for other countries.

“As homicide rates decreased in municipalities with larger population sizes, it increased in municipalities with smaller population sizes,” says study lead author Dr. Elaine Nsoesie, assistant professor of global health at BUSPH.

“This is a warning to other countries,” says study senior author Adauto Martins Soares Filho, a technologist in health information systems in the Department of Health Surveillance at Brazil’s Ministry of Health.

Brazil has a severe epidemic of lethal violence driven by drugs and arms trafficking and by land conflicts. Over the last two decades, the country has seen homicide rates go down in large cities even as the national rate continues to climb: Brazil had 63,880 homicides in 2017 (the most recent year with available data), its highest ever recorded.

To understand how Brazil’s geography of violence has changed, the researchers used data from the Brazil Ministry of Health Mortality Information System and sociodemographic data from the Brazil Institute of Geography and Statistics, and created space-time models to identify patterns in homicide rates and assess the roles of different structural factors.

The researchers found that the strongest predictors for an area having a higher homicide rate included higher crude domestic product, being near an international border, and having a larger proportion of the population between the ages of 15 and 29. They also found that, as efforts to reduce violence in large cities succeeded, that violence appeared to simply move to neighboring, less urban areas.

“We propose the need for policies that account for possible spatial spillover as interventions are focused on particular locations,” Nsoesie says. “We also propose adopting policies that address the increase in poverty rates in specific populations that tends to occur in tandem with economic development.”

But Nsoesie and Soares Filho acknowledge that the challenges are enormous, especially now that the COVID-19 pandemic threatens to reverse decades of progress in many areas–and as the government enacts policies that threaten to increase fatal violence, such as the country’s 2019 law loosening gun ownership restrictions.

“A successful trajectory in reducing homicides depends on the political will and capacity to lead the construction of a peaceful, just, and inclusive society,” Soares Filho says.