Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who has denied the severity of the coronavirus pandemic and ridiculed social distancing, tested positive for the novel coronavirus on July 7 after showing mild symptoms.

Bolsonaro is one of 1.9 million confirmed COVID-19 victims in coronavirus-wracked Brazil. But as a white, wealthy and powerful man, he is not a member of the most hard-hit group. Data shows that Black Brazilians and Indigenous people are getting sick and dying at much higher rates.

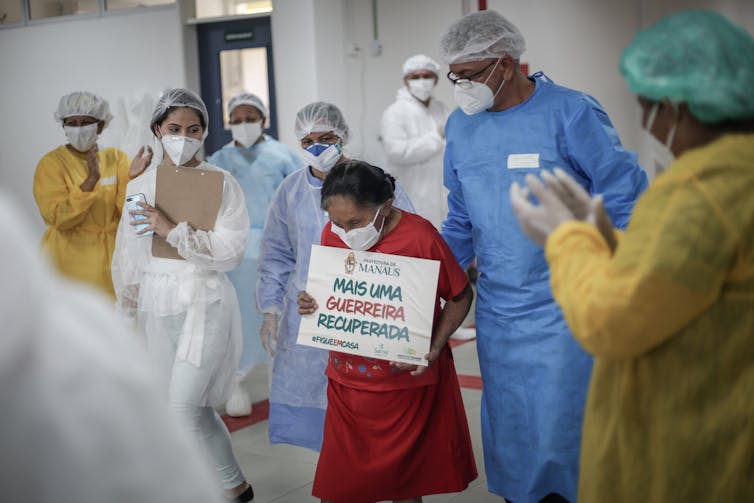

Indigenous communities face particularly daunting odds to survival during the pandemic. Most of Brazil’s roughly 896,000 Indigenous people live in the Amazon region, where the nearest hospital may be days away by boat and offer limited care. Indigenous Brazilians also have higher rates of malnutrition, anemia and obesity than the general population – risk factors for severe COVID-19.

As of July 6, Brazil’s Health Ministry reported 7,958 COVID-19 infections among Indigenous people and 171 deaths. The National Committee for Indigenous Life and Memory, an advocacy group for Indigenous people during the pandemic, estimates 12,000 infections and 400 deaths.

The situation is dire for the Amazonian Yanomami people. If current trends continue, 5,600 Yanomami – or 40% of their entire population – could become infected with COVID-19, according to a report from Brazil’s Indigenous Environmental Institute.

COVID-19 is just the latest deadly threat to Indigenous people under Bolsonaro, whose policies and rhetoric are so openly hostile that they essentially amount to a campaign of genocide, our research finds.

What is genocide

Under Bolsonaro, who took office in January 2018, Brazil has dismantled environmental protections of the Amazon, allowing deforestation to spike. He has also curtailed the land rights of Indigenous people and turned a blind eye to illegal mining, logging and farming operations on their territory.

In late 2019, those policies led two leading Brazilian human rights organizations to report Bolsonaro to the International Criminal Court, alleging that the right-wing leader was “inciting genocide” against Indigenous people. This case is still pending.

Under international law, the crime of genocide requires “intent to destroy, in whole or in part,” a group based on their nationality, ethnicity, race or religion. While genocide often involves explicit killing, it can also include causing serious harm to a population and destroying their way of life.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]As scholars of mass atrocity prevention and Indigenous rights, we have watched with alarm as Brazil showed warning signs that this latter, slower type of genocide was underway. Now COVID-19, which is actually killing Indigenous people by the hundreds, could be the final straw.

Warning signs

In theory, many Brazilian Indigenous people should be well situated to escape COVID-19 exposure. An estimated 10,000 live in voluntary isolation across the Amazon, separated from broader Brazilian society. Many others have only limited contact with the outside world.

Their rights to self-determination and isolation are confirmed by two international agreements on indigenous rights, both of which Brazil signed. In recent years, however, loggers, miners and farmers have aggressively violated these land rights and set up shop in the Amazon, sometimes with the Bolsonaro government’s explicit endorsement.

The illegal land grabs have worsened during the pandemic, as the world’s attention turned away from the Amazon. The number of non-Indigenous gold miners working on Indigenous lands in Brazil increased from 4,000 in 2018 to over 20,000 so far in 2020. Such incursions risk bringing the coronavirus into Indigenous communities.

The systematic violation of Indigenous land rights also endanger their very survival.

Indigenous people have lived in the Amazon for centuries, protecting the rainforest in a manner that not only supported their traditional way of life but also protected this global natural resource. Historically, they could count on at least minimal government regulations intended to defend the Amazon rainforest, though deforestation has long been a challenge.

But Bolsonaro does not believe in defending the Amazon or its inhabitants. One of his first acts in office was to roll back environmental protections. Deforestation of the Amazon has increased 34% since 2018, according to the Brazilian Amazon monitoring program. Deforestation of Indigenous lands is up almost 80%.

Illegal property seizure and rights violations like those experienced by Indigenous Brazilians under Bolsonaro are known warning signs of genocide. So is the physical destruction of a persecuted group’s homeland. According to the UN, “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its

physical destruction in whole or in part” constitutes genocide.

Denying the humanity of a group is another frequent precursor to genocide, history shows. Before the Holocaust, for example, Nazis referred to Jews as rats.

Bolsonaro has not gone so far as to characterize Indigenous Brazilians as vermin. But he refers to them using derogatory language.

“The Indians do not speak our language, they do not have money, they do not have culture,” he told Campo Grande newspaper in 2015, when he was still a congressman. Earlier this year, Bolsonaro said Indigenous people exposed to the outside world are “increasingly becoming human beings, like us.”

Time for intervention

Land grabs, insufficient health care, deforestation and stigmatization all threatened Indigenous Brazilians before the pandemic. Genocides can be that way. They are a process, not sudden, isolated events.

Risk factors and warning signs can smolder for years in a country. Then a “trigger” like COVID-19 ignites them, resulting in mass death.

We’re not alone in making this dire forecast. On June 29, a Brazilian indigenous rights organization and six political parties jointly requested an order of protection for Indigenous people during the coronavirus pandemic to prevent genocide from occurring.

The plaintiffs insist that the government must provide adequate health care to all Indigenous Brazilians; physically secure Indigenous land to prevent illegal miners, loggers and others from entering; and expel those who do trespass. Failing these emergency measures, they assert, Brazil’s Indigenous peoples face extinction.

If the court grants their request, there’s no guarantee the government will comply. But it could saves lives. For indigenous communities with just a few hundred members, that may make all the difference.![]()

Nadia Rubaii, Co-Director, Institute for Genocide and Mass Atrocity Prevention, and Professor of Public Administration, Binghamton University, State University of New York and Julio José Araujo Junior, PhD student of law, Rio de Janeiro State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.