The United States and Brazil have much in common when it comes to the coronavirus.

Both are among the world’s hardest-hit countries, where hundreds die daily. Their like-minded presidents, Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro, have both been widely criticized for their poor handling of the pandemic.

And in both countries the virus is disproportionately affecting black people, the result of structural racism that dates back to slavery.

Legacy of slavery

Brazil forcibly brought some 4 million enslaved Africans into the country over three centuries, more than anywhere else in the Americas. About half its 209 million people are black – the world’s second largest African-descendant population after Nigeria.

Modern Brazil never had legalized racial discrimination like Jim Crow, but race-based inequalities are deeply entrenched. Despite a persistent myth of Brazil as an integrated “racial democracy,” employment discrimination and residential segregation limit opportunity for black people.

These and other factors translate into lower life expectancy, education and standards of living for Afro-Brazilians. Black Brazilians live, on average, 73 years – three years less than white Brazilians, according to the 2017 National Household Survey. The U.S. has a nearly identical life expectancy gap between races.

Because government data in Brazil is not automatically collected by race or ethnicity, though, the health impacts of racism can be hard to measure. Bolsonaro’s administration did not require the collection of COVID-19 racial data until late April, well into the pandemic, after much pressure. It has yet to release that information.

Regardless, by April the Brazilian Health Ministry had already flagged high COVID-19 death rates among Afro-Brazilians, a category that includes people who identify as “black” or “brown” in the census. Officials in hard-hit São Paulo had also announced that mortality rates among COVID-19 patients were higher among black residents.

Now, data collected in May by outside researchers for over 5,500 municipalities shows that 55% of Afro-Brazilian patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 died, compared to 34% of white COVID-19 patients.

Health and racism

We are health researchers – one American, one Brazilian – who for many years have studied how racial disparities in Brazil affect black people, looking at everything from sickle cell anemia to reproductive health.

Our research over the past two months finds structural racism – in the form of high-risk working conditions, unequal access to health and worse housing conditions – is a major factor shaping Brazil’s COVID-19 pandemic.

For over a decade, black activists and public health researchers have been pointing out that institutional racism creates worse health outcomes for Brazil’s black population. Black Brazilians experience higher rates of chronic illnesses like diabetes, high blood pressure, and respiratory and kidney problems due to food insecurity, inadequate access to medicine and unaffordable prescriptions.

Racism itself also takes a severe physical toll on black people. Studies in the United States demonstrate that daily experiences of racism and discrimination can lead to dangerously high stress hormones and diminish the body’s ability to fight disease. Racial bias from medical professionals then compounds poor outcomes for black patients.

Unlike the U.S., Brazil has free, universal health care. But its public hospitals have been woefully underfunded since a deep recession that began in 2015.

Intensive care beds are now in short supply at public hospitals in several cities fighting coronavirus outbreaks. This is especially detrimental to black COVID-19 patients, since Afro-Brazilians rely more heavily on the public health system than white Brazilians, who often have private health insurance through their jobs.

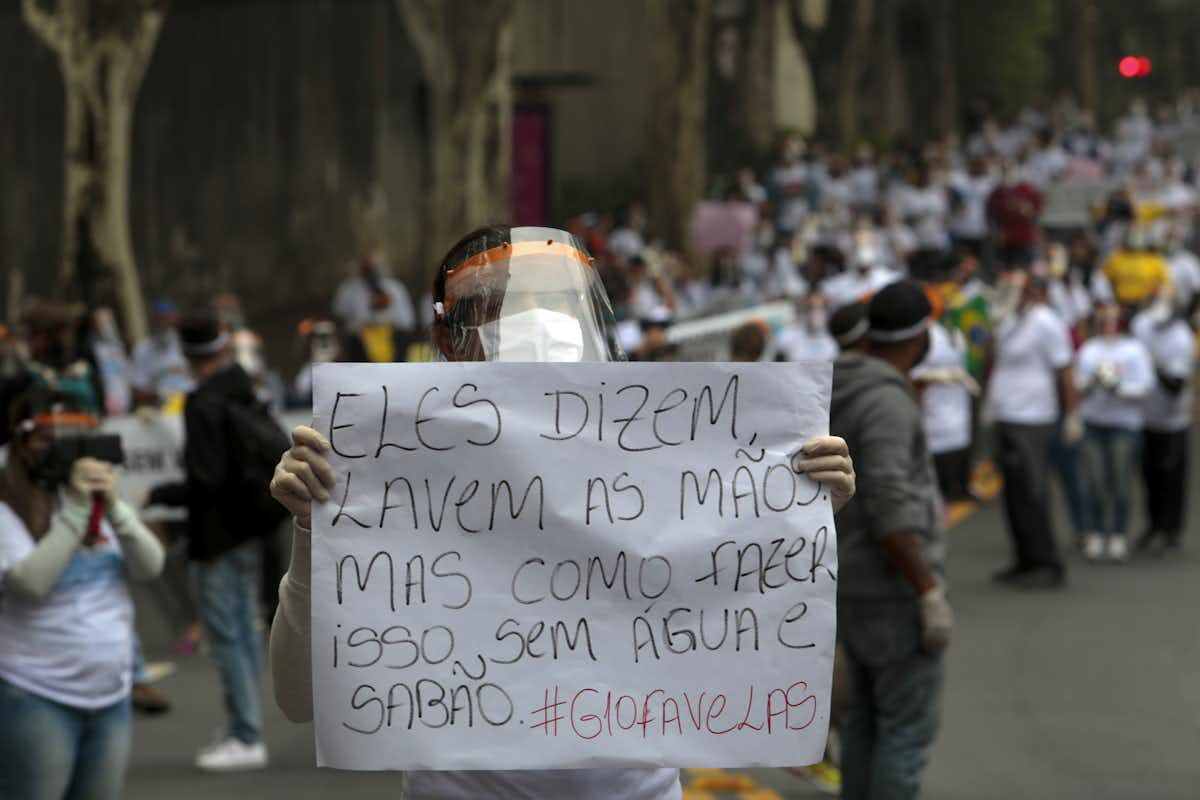

Lucas Silva/picture alliance via Getty Images

Poverty and exposure

Extreme economic inequality is another critical factor shaping the general health of Afro-Brazilians. With the top 10% of the population earning 55% of domestic income, Brazil trails only Qatar in concentration of wealth, according to a 2019 United Nations report.

Few, if any, Afro-Brazilians rank among Brazil’s super-rich. National household survey data shows that black and brown Brazilians make far less money than white Brazilians, even with equivalent educational background. The racial wage gap in Brazil actually outweighs the gender wage gap: White women earn up to 74% more than black men.

Generally speaking, the higher the salary, the less likely Afro-Brazilians are to have a job. Many work in the informal and service sectors, as house cleaners or street vendors. Others are self-employed or unemployed.

During the pandemic, this economic insecurity severely lessens Afro-Brazilians’ ability to socially distance and makes them highly dependent on staying in their jobs despite the health threat.

Maids, for example – most of whom are black women – are proving to be a high-risk group. Domestic workers were among Brazil’s first COVID-19 deaths.

Neighborhood risks

Brazil’s coronavirus outbreak originated in wealthy neighborhoods whose residents had traveled to Europe, but the disease is now spreading fastest in its poor, dense, long-neglected urban neighborhoods.

Just over 12 million Brazilians, most of them black, live in such informal urban settlements, from Rio de Janeiro’s favelas to the “peripheries” of São Paulo. These areas have inadequate access to water and sanitation, making it difficult to follow basic hygiene recommendations like washing one’s hands with soap.

So while the disparate impact of COVID-19 on black Brazilians was not inevitable, our research explains why it’s unsurprising.

The racism that pervades nearly every facet of Brazilian society increases black people’s exposure to the virus – then reduces their ability to get to quality care.

Kia Lilly Caldwell, Professor, African, African American, and Diaspora Studies, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Edna Maria de Araújo, Professor of Public Health and Epidemiology, State University of Feira de Santana (Brazil)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.