Evo Morales is hardly Bolivia’s first president to be ousted in a mass uprising.

Both of his immediate predecessors – Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada and Carlos Mesa – resigned after waves of mass protest. So did at least seven other Bolivian presidents since 1870.

The power of the Bolivian people is so formidable that former president Mesa, upon resigning in 2005, declared the country “ungovernable.”

Bolivia’s new interim president, Jeanine Añez, may well echo the sentiment. Deadly protests have gripped Bolivia since she took power on Nov. 11, and Morales’ socialist party, MAS, retains a two-thirds majority in both the lower and upper houses of Congress.

Añez, a former senator from Bolivia’s weak opposition, has virtually no power. Her party stands little chance of passing legislation. And protests against her government continue.

Power to the people

Throughout Bolivian history, protests have been an important way indigenous people and rural peasants, long excluded from the halls of power, have made their voices heard.

Whether to force more equitable land distribution in the 1952 Bolivian National Revolution, demand the return of the coastal province conquered by Chile in 1883 or call for the nationalization of resources such as oil and gas, these marginalized communities have often earned major concessions via protest.

As I have argued in my political analyses of the South American country, Bolivian government institutions are so weak that effective governance requires at the least some populist compromise.

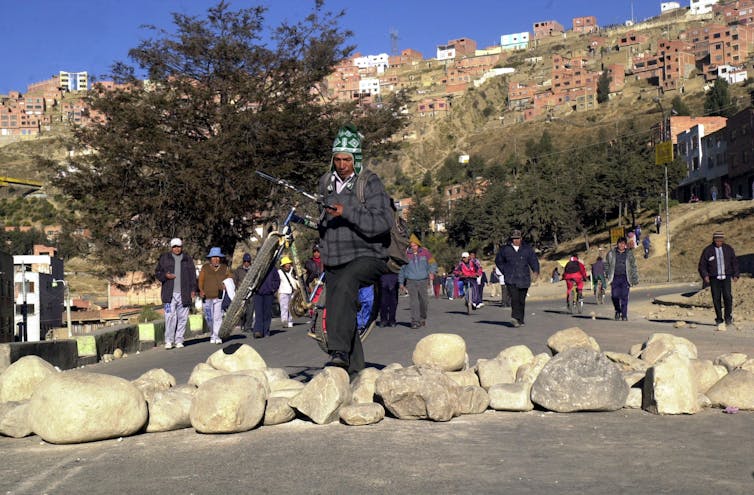

Indigenous Bolivians organize massive marches, blocking roads into major urban centers to prevent food and fuel from entering and exploding dynamite to highlight their dismay. By paralyzing cities, including the seat of government, these indigenous protest strategies have effectively overwhelmed numerous Bolivian governments.

That’s how Morales himself rose to power: He was the highly visible leader of the 2003 and 2005 protests that ousted his immediate predecessors.

A military mutiny

The shocked tone of Morales’ last press conference as president, held on Nov. 10, made clear his outrage at being on the receiving end of a similar mass mobilization.

Morales was forced to resign amid protest after he declared victory in Bolivia’s contested Oct. 20 presidential election. Few doubt that he won the race, however. What was in dispute is whether he won by a margin of 10% – enough to avoid a runoff with his closest competitor, the former president Carlos Mesa, who 12 years ago resigned amid protests.

Morales and his most ardent supporters said he beat Mesa by just over 10%. Opposition parties, their supporters and the Organization of American States found the narrow margin suspicious and called for a new vote.

Morales eventually agreed amid wild protest, but not before a police mutiny encouraged violence against his political allies. The military announced that it would not use force to subdue anti-Morales protesters. Soldiers looked on as demonstrators looted and burned to the ground the houses of some MAS party members.

Ultimately, the police and military compelled Morales to resign. It was clear he had lost control.

Complete paralysis

Yet Morales opponents weren’t necessarily eager to see Carlos Mesa, who still commands very little devotion, elected president. They just wanted Morales out. And though Morales’ base has frayed somewhat over 14 years due to his government’s pursuit of natural gas development in indigenous areas, he remains by far the most popular politician in Bolivia.

Morales is now leading by tweet from exile in Mexico, urging his supporters to wage their own mutiny against the new interim government and hinting at his return.

“[T]he struggle continues,” he wrote in a Nov. 15 tweet that painted Bolivia’s history as a fight between indigenous people and the powers that would oppress them. “I will return and I will be millions.”

Massive protests have virtually paralyzed Bolivia, as indigenous roadblocks keep food and fuel from La Paz and angry protesters attempt to march on the presidential palace itself. The city of Cochabamba and its surroundings are also rocked by violent protest. Thus far, Bolivian military and police have shot dead at least 14 people.

Ungovernable country

While the new government has the support of both the Bolivian military and the police, this does not make the country governable.

Añez, ruling without a mandate, has only one real responsibility: to organize elections. The Congress has now voted on a plan to hold another presidential vote, although no date has been set, and Morales has agreed he will not be a candidate.

Setting new elections without Morales is a win for the opposition in Bolivia and a fundamental step toward restoring a semblance of normalcy.

But Morales’ base is unlikely to simply accept the results, whatever they may be.

To paraphrase the Bolivian historian Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, the indigenous Bolivians who adore Morales are “oppressed but not defeated.”

Marten W. Brienen, Lecturer in Global Studies, Oklahoma State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.