Guatemala’s next leader will be Alejandro Giammattei, a right-wing former national prison director.

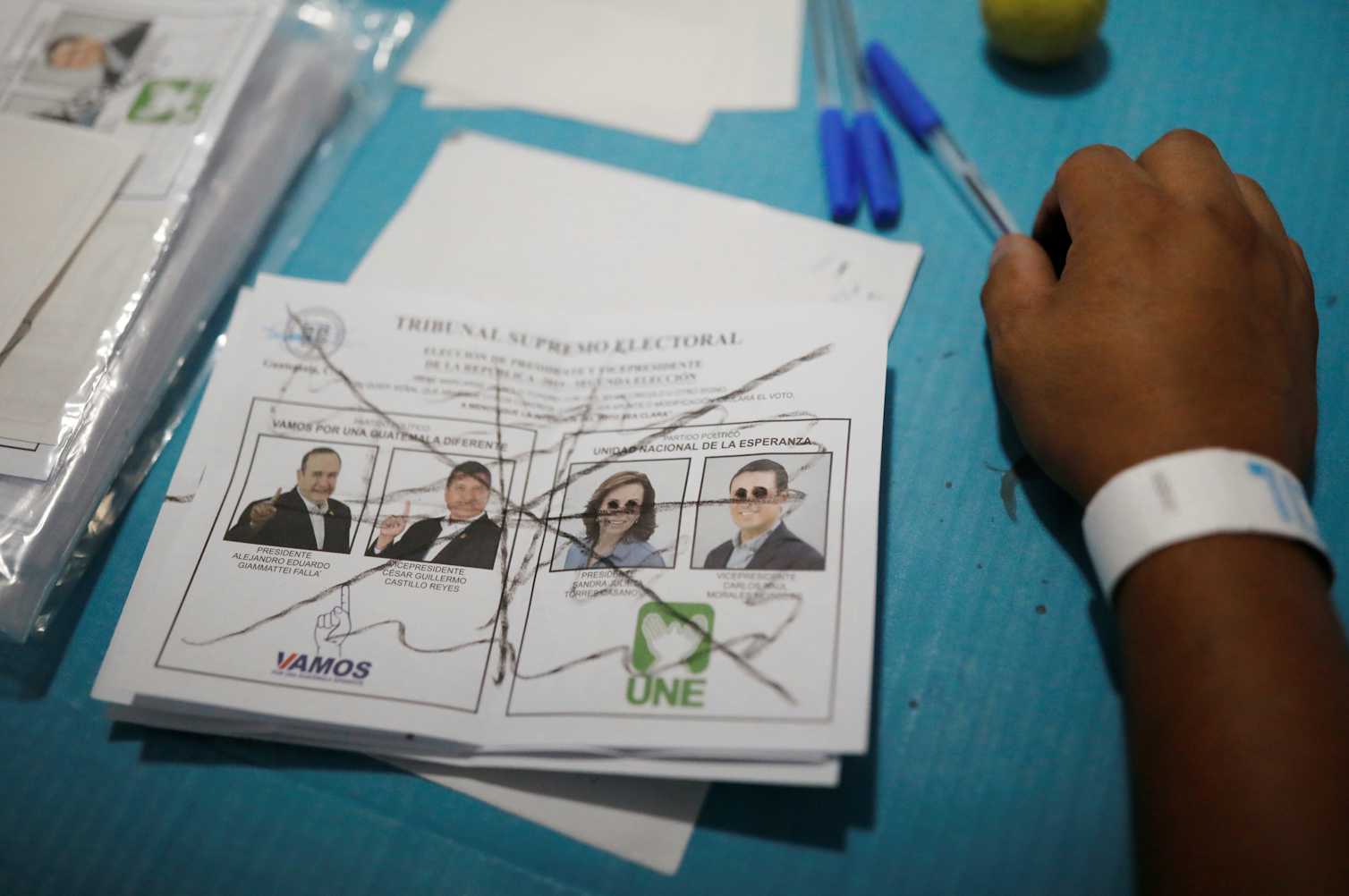

With 58% of votes, Giammettei beat former first lady Sandra Torres by 16 points in the second round of Guatemala’s election on Aug. 11. It was his fourth presidential bid.

As a candidate, Giammattei spoke of creating jobs and fighting crime in the poor, violence-gripped Central American country. But his campaign offered few policy proposals beyond taking a hard line against gangs like MS-13 that operate with impunity in Guatemala, building new prisons and reimposing the death penalty.

Giammattei hasn’t yet agreed to implement Guatemala’s controversial recent agreement with the Trump administration to stop Central American migrants from crossing through Guatemala.

The 63-year-old Giammattei’s base includes former military members, the far right, evangelicals and business leaders – essentially the same electorate that put outgoing President Jimmy Morales in power. But polling suggests Giammattei won primarily due to the extreme unpopularity of his opponent, who has a history of corruption allegations.

Guatemalans were deeply unenthusiastic about both candidates. Just 42% of registered voters voted, the lowest percentage since the country’s civil war ended in 1996. Nearly 6% of them cast blank or spoiled ballots, apparently in protest.

Many Guatemalans expressed fear that no matter who won the runoff, this election would mark the end of Guatemala’s decade-long fight to root out massive government corruption.

Giammattei is an ally of President Morales, who is under investigation for campaign finance violations. His inner circle of former generals and elite power brokers who have ruled the country for decades also backed the disgraced former President Otto Pérez Molina, who resigned amid scandal in 2015 and was jailed hours later for corruption.

Justice no more

As a longtime researcher on justice in post-civil war Guatemala, I have grave concerns about Giammattei’s commitment to restoring the rule of law.

Giammattei is closely associated with the old military intelligence groups that have dominated Guatemalan politics behind the scenes since its bloody, decades-long civil war ended in the 1990s.

His tenure as national director of prisons was tainted when seven inmates were killed under suspicious circumstances in 2006 at Guatemala’s notoriously lawless Pavón prison.

According to prosecutors, the killings were committed by a prison death squad that worked inside jails, with administrators’ explicit approval, to exterminate the “dregs” of society and “enemies of the state.” Three of the killers were convicted of murder in Guatemala for the prison deaths.

Giammattei was charged with conspiracy but acquitted in 2013. Last year a Swiss appeals court sentenced his accused co-conspirator, former police chief Edwin Sperisen, to 15 years in prison for the murders.

Giammattei was not expected to become Guatemala’s president.

Early in the race the clear front-runner was Thelma Aldana, Guatemala’s corruption-busting former attorney general. But in May she was barred from the race for alleged financial mismanagement. That bumped Sandra Torres into first place, with Giammattei running a distant second.

Many saw the ruling against Aldana as politically motivated.

As attorney general from 2014 to 2018, Aldana worked closely with the United Nations-backed anti-corruption panel known as CICIG. Since its creation in 2007, CICIG has prosecuted three former presidents and more than 600 other high-ranking officials in Guatemala for everything from money laundering and embezzlement to ties with organized crime.

When President Morales expelled its lead prosecutor earlier this year, Aldana vocally protested. She has since fled the country after receiving death threats.

Giammattei says he will pursue the fight against endemic corruption but he opposes the CICIG, which supported his prosecution in the Pavón Prison case. Despite 72% popular support, the commission is now due to close in September.

Giammattei has offered no concrete plan to continue cleaning up Guatemala’s government. Without the CICIG’s investigators and prosecutors, Giammattei is unlikely to pull the country out of the morass of kleptocracy, violence and extreme poverty that sends thousands of desperate Guatemalans abroad each year.

Trouble ahead, trouble behind

Through bribery, coercion and threat of violence, criminal cartels have infiltrated Guatemala’s government over the last 20 years.

A CICIG investigation found that half of political party financing comes from organized crime and corruption. In Guatemala’s Congress, dirty legislators known to be on the take are locally regarded as the “Pact of the Corrupt.”

The largest bloc in the incoming Congress, which takes office Jan. 1, will be from Torres’ National Unity of Hope party. Just 17 of 158 Guatemalan lawmakers belong to Giammattei’s Vamos Party.

A small bloc of legislators will come from a new center-left party called Semilla, or “Seed,” which nominated Aldana as its presidential candidate. Semilla’s presence ensures Giammattei will have some vocal opposition in Congress.

A conservative majority of lawmakers is expected to try again to pass a controversial amnesty law that would pardon former military officials convicted of crimes against humanity during Guatemala’s civil war and prevent those accused of human rights violations from being prosecuted.

Given his military ties, Giammettei would likely sign such an amnesty bill into law.

Guatemalan judges who, with the support of the CICIG, have put former military officers and corrupt politicians in prison have faced unfounded investigations against them and threats to their safety. So have human rights actvists and environmental defenders.

These attacks on the rule of law in Guatemala would ordinarily draw criticism from the United States. Now they are met with silence, both from the Trump administration and Guatemala’s new president-elect.

This is an updated version of an article original published on June 21, 2019.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]Naomi Roht-Arriaza, Distinguished Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.