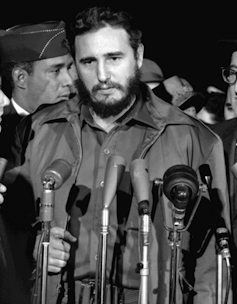

Leadership changes don’t happen often in Cuba – there’s been just one since 1959, in fact. That was in 2006, when President Fidel Castro fell ill and was replaced by his brother Raúl.

Raúl Castro turned out to be a real agent of change. But after two terms as president, the 86-year-old is stepping down. On April 19, the National Assembly will meet to pick Cuba’s next leader.

And for the first time in six decades, his last name will not be Castro.

This is a momentous occasion — one of the most important I’ve seen in 40 years of studying and writing on Cuba. For any state born in revolution, the first transfer of power to a new generation is always politically risky.

Raúl Castro’s successor must grow Cuba’s economy, contend with the United States and deal with a growing chorus of critics. And he will have to tackle these tasks while the Communist Party is still dominated by Fidel’s revolutionary comrades, who have sharp disagreements on all these issues.

Who can fill Castro’s shoes?

The clear favorite to replace Raúl Castro is Cuba’s 57-year-old First Vice President Miguel Díaz-Canel. His ascension would represent a transfer of power away from the “historic generation” that waged Cuba’s 1959 revolution, many of whom are now pushing 90.

In 2011, Raúl Castro mandated a two-term limit for senior government and party officials. It “is never positive” for the elderly to cling to power, he declared.

But the charisma of Fidel Castro, who died in 2016, has been a pillar of Cuba’s regime. Díaz-Canel – a trained engineer who worked his way up from provincial party leader to first vice president – will have to earn his authority through performance.

Those who have followed his career say Díaz-Canel is a seasoned, pragmatic politician. He is apparently a bit stiff in front of large audiences but relaxed and congenial in small groups – much like his mentor, Raúl Castro.

As president, Díaz-Canel would still benefit from Castro’s experience and authority. Castro remains first secretary of the Communist Party – Cuba’s only party – until 2021.

This is arguably a post more powerful than the presidency. The party leadership makes all major economic, social and foreign relations policies, which the president is obliged to carry out.

So I don’t expect any drastic changes in direction from Díaz-Canel – at least, not right away.

The leadership transition is still significant, though. It marks the first time that the leader of the Communist Party and the leader of the Cuban government will be different people. Both Fidel and Raúl Castro held both positions simultaneously.

Cuba must now sort out the lines of authority between party and state. As Díaz-Canel staffs government ministries with his own team, he will gain ever more control over how policy is interpreted and implemented.

Is Cuba in for a change?

The new president will face some tough issues.

Cuba’s economy is struggling, dragged down in particular by the dual-currency system Fidel Castro adopted in 1994 to attract cash remittances from Cuban expats. Raúl Castro has declared that currency reunification “cannot be delayed any longer.”

But turning two currencies into one is a tricky business with unpredictable economic consequences. And unlike almost every other country in the world, Cuba cannot turn to the International Monetary Fund or World Bank for support because it withdrew from them after the revolution.

Díaz-Canel will also face pressure to reinvigorate the Cuban economy by pushing ahead with Raúl Castro’s controversial economic reform program. Castro loosened restrictions on private enterprise and foreign investment in Cuba early in his tenure, but the pace of change has since slowed.

If Díaz-Canel opens up Cuba’s economy too quickly, he’ll alienate Communist Party conservatives. Going too slowly will anger reformers, not to mention frustrate the Cuban people.

Another contentious issue facing Cuba’s incoming president is freedom of expression. Public criticism of the regime has grown as more Cubans connect to the internet. Last year, hard-liners launched a campaign vilifying critical bloggers, which – to many onlookers’ surprise – Díaz-Canal supported.

Other prominent Cubans pushed back, though, and the campaign ultimately ended without any of the targeted web sites being closed down.

Castro balanced conflicting factions with a delicate strategy he described as reform “without haste, but without pause.” He also benefited from unquestioned authority in the party. Díaz-Canel will have to establish his own legitimacy.

US-Cuba relations in flux

Finally, Díaz-Canel must deal with the mercurial Trump administration, which has largely outsourced Cuba policy to the conservative Cuban-Americans in Congress.

This faction, lead by Sen. Marco Rubio, a Republican from Florida, denounced President Barack Obama’s restoration of U.S.-Cuba relations. Although Trump declared he was “cancelling” Obama’s policy, he has so far left most Obama-era commercial openings untouched.

In October, Trump further battered bilateral ties by downsizing the U.S. Embassy in Cuba after U.S. government personnel suffered unexplained health problems there. He also expelled 17 Cuban diplomats from Washington.

Recent Trump appointments do not bode well for the future of U.S.-Cuban relations. The incoming secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, was a vocal opponent of Obama’s rapprochement with Havana. And national security adviser John Bolton once deemed Cuba part of an “axis of evil,” falsely accusing it of developing biological weapons.

Anticipation and trepidation

In December, I was in Havana, a city where the benefits of Raúl Castro’s economic reforms are most tangible. Cubans I spoke with there seemed ready for younger leadership and excited about the impending power transition.

But 80 percent of Cubans have always had a Castro as their president. So the anticipatory mood is leavened by trepidation. People fear that change at the top could bring instability.

![]() If Díaz-Canel can deliver on the economy – the top priority for most Cubans – he’ll be judged a success. If not, he will face a rising tide of discontent from a population impatient for change.

If Díaz-Canel can deliver on the economy – the top priority for most Cubans – he’ll be judged a success. If not, he will face a rising tide of discontent from a population impatient for change.

William M. LeoGrande, Professor of Government, American University. This article was originally published on The Conversation.