In the Andean foothills of central Colombia, rural families are surrounded by rivers, rainfall, and lush green valleys. Yet for millions of people, turning on a tap does not mean safe drinking water — it means risk.

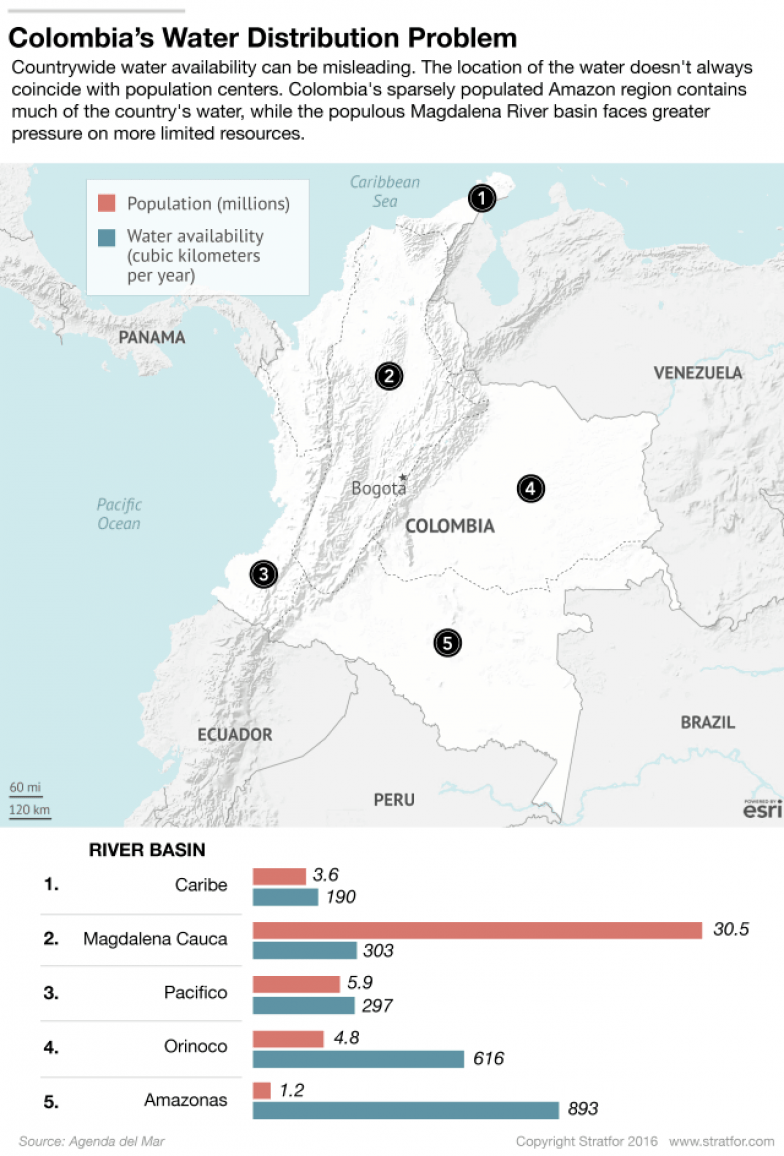

A recent study by Colombia’s Ministry of Housing and the National Department of Planning revealed that more than 3.2 million Colombians in rural areas lack access to safe drinking water, despite living in one of the most water-rich countries in the world. Infrastructure designed to treat and deliver potable water, as well as handle wastewater, remains dangerously underdeveloped outside of urban areas.

The Colombian government has pledged over 9.2 billion USD in infrastructure investments, some through public-private partnerships, to close the gap. But experts warn that money alone won’t solve the problem.

“Colombia doesn’t have a water availability crisis — it has a water management crisis,” said Ana María González, a hydrologist advising regional governments. “The challenge is not the river — it’s what happens between the river and the faucet.”

As rural communities battle rising health concerns, local aqueducts run by citizen groups are stepping in — offering a grassroots, if fragile, solution. But these efforts need support, both financially and institutionally, and time may be running out.

A System Under Strain

Colombia ranks among the top 10 countries in freshwater availability per capita. Yet service coverage is highly unequal:

-

Urban access to potable water: ~94%

-

Rural access to potable water: < 70%

-

Rural wastewater treatment: < 40%

In rural areas, informal water systems — often poorly regulated and untreated — serve small towns and dispersed communities. Untreated wastewater from homes and agriculture is frequently discharged into rivers, creating environmental and health hazards.

The lack of wastewater infrastructure, according to the Ministry of Health, is linked to a resurgence of waterborne diseases like diarrhea, hepatitis A, and parasitic infections, especially in children.

Decentralization Without Coordination

Decentralization Without Coordination

One core issue is institutional fragmentation. Since water services were decentralized in the 1990s, local governments and small utilities — many under-resourced — have been responsible for water delivery.

While the intent was to bring governance closer to communities, the result has often been uncoordinated policies, funding gaps, and little oversight. The National Water Plan has struggled to synchronize rural and urban service models.

Compounding the issue, many municipalities lack technical expertise or planning capacity to apply for national infrastructure funding, let alone manage large-scale projects.

The Role of Community Aqueducts

In the absence of state services, community aqueducts — often led by local associations — have emerged as essential infrastructure for survival. Particularly in regions like Boyacá, Cauca, and Santander, these systems:

-

Manage their own water intake, distribution, and (in rare cases) treatment.

-

Operate on volunteer labor or small fees.

-

Often serve hundreds or even thousands.

Yet most are not formally recognized under Colombian law, limiting access to public funds or technical support. Climate variability has made their work harder.

In 2024, droughts driven by El Niño conditions dried up water sources in over 150 municipalities, many served solely by community-run systems.

“We’re protecting our watershed with machetes and buckets,” said Mario Quintero, who helps manage a community aqueduct in Boyacá. “But it’s not enough. We need help.”

Private Sector: Interested But Hesitant

The Colombian government has actively encouraged private investment in water and sanitation projects, positioning them as part of the country’s broader development and climate adaptation strategy.

Several international firms, including Veolia, Aqualia, and Acciona, have explored projects in Colombia’s mid-sized cities and are watching rural tenders closely.

Opportunities for the private sector include:

-

Small-scale wastewater treatment systems

-

Rural desalination plants (Caribbean region)

-

Off-grid purification technologies

-

Infrastructure-as-a-service for municipalities

However, firms face several barriers to entry, including:

-

Regulatory instability

-

Difficulty securing long-term water rights

-

Risk of political turnover affecting contracts

-

Low payment capacity in rural communities

As one executive from a European water firm said anonymously: “We want to invest, but there must be guarantees — on tariffs, enforcement, and continuity.”

Government Strategies and Limitations

President Gustavo Petro’s administration has pledged a national “Water for All” program, which aims to:

-

Extend potable water services to 1.5 million new rural users by 2030.

-

Increase wastewater treatment coverage by 20%.

-

Protect aquifers and watershed ecosystems through land conservation.

The strategy leans on public-private partnerships (PPPs) and multilateral financing, including from the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank. In 2024 alone, over 40 water-related infrastructure projects were approved under Colombia’s 5G infrastructure program.

But critics argue the implementation pace is too slow — and too urban-focused.

“The current model privileges large cities and regions with higher tax bases,” said María Isabel Ruiz, a policy analyst with the Universidad de los Andes. “Rural Colombians are once again treated as second-class citizens.”

Water Security as National Security

Beyond health and development, experts increasingly link water insecurity to broader instability.

In regions like Cauca, Nariño, and Putumayo, water access is deeply intertwined with:

-

Conflict dynamics: Guerrilla groups and criminal organizations have targeted water infrastructure.

-

Illegal mining: Mercury pollution from illegal gold mining poisons rivers used for drinking.

-

Forced displacement: Communities fleeing violence often resettle in areas with no water systems.

In this context, water infrastructure is not just a development issue — it’s a national security imperative.

Policy Recommendations: A Path Forward

-

Strengthen Community Aqueducts

-

Formalize and regulate existing systems.

-

Provide training and technical support.

-

Create public funding windows specific to these operators.

-

-

Develop Rural-Specific Service Models

-

Encourage modular or decentralized water systems.

-

Tailor financing to low-density, low-income contexts.

-

Foster partnerships between ESPs and community groups.

-

-

Incentivize Private Sector Participation

-

De-risk investments with blended finance tools.

-

Offer tax breaks or guarantees for rural projects.

-

Standardize PPP frameworks across regions.

-

-

Align Environmental and Infrastructure Goals

-

Protect source watersheds through reforestation and PES (payment for ecosystem services).

-

Link water programs to climate adaptation and disaster preparedness funding.

-

-

Integrate Water Policy into National Security Planning

-

Map high-risk zones for water insecurity.

-

Ensure contingency planning for drought and displacement.

-

Include water resilience in peacebuilding frameworks.

-

Conclusion: Turning the Tide

Colombia’s rural water crisis is emblematic of a global paradox: abundance without access.

The solutions exist — in technology, in governance, in local ingenuity. But they require a coherent, inclusive, and sustained commitment from both the state and the market.

Water security is not only about pipes and pumps — it is about justice, health, and peace. And in the Colombian countryside, it is a test the country can no longer afford to fail.

– Use Our Intel