The Peruvian government has a clear development agenda for its Amazon rainforest regions. Oil extraction is already happening on a large scale. That will be supported by significant investment in new gas pipelines, proposed hydroelectric dams and other large transport projects.

But what do people who actually live in the region make of all this? In my research, I have shown that Peru’s development plans are deliberately restricting the ability of local citizens to provide consent for these projects.

This is no accident. Most people living in Peru’s Amazon regions are indigenous, a group of people who remain excluded and discriminated against. According to one former president, indigenous people are an obstacle to development, “artificial communities that own 200,000 hectares on paper but only farm 10,000 hectares while the rest is idle property”.

Peruvians are free – on paper

Peru is a young democracy which has only properly held elections since 2001. Its constitution sets out significant rights for its citizens including the “freedom of information, opinion, expression” and the right to their “own voice and image”. Peru is also a member of several important regional human rights bodies and has signed relevant international treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Together, these further enshrine citizen rights and the state’s obligations. On paper at least, Peruvians have an open political environment in which to make their voices heard.

However, Peru’s democracy is not perfect and has been evaluated as “flawed” and “defective” by international studies. While citizens have rights, the country’s weak state institutions mean that it can fail to uphold or implement them. More troublingly, a closer look at Peru’s freedom of voice surrounding development projects finds a far more restrictive political environment for citizens.

A dangerous place for activists

Research has found that governments across Latin America have routinely tried to criminalise social protest, especially in relation to large development projects.

This is evident in Peru. Its broad terrorism law has been criticised due to the way it has been applied to non-terrorist acts like protests against development projects or over indigenous issues. Other laws have built on this. For example, a 2008 decree removed a requirement for the government to declare a state of emergency before deploying the army. Equally, in September 2010, a new law permitted the armed forces to be used against protesters and regulated the use of lethal force against “hostile groups”.

None of this seems to have worked: according to Peru’s human rights ombudsman, social conflicts which turn violent have resulted in 271 deaths since 2006, while Global Witness says 50 environmental and human rights defenders were killed in Peru between 2010 and 2015. Other groups that campaign on these issues have also been attacked by the state to discredit them. For example, anti-mining groups have been labelled “anti-mining terrorists” by the state, a term used deliberately to associate them with the Shining Path, a Maoist terrorist insurgency that ravaged Peru in the 1980s and 1990s.

Consultation is failing

Peru has two main mechanisms through which the public can be consulted: a law of prior consultation, and environmental impact assessments. Both have improved things, but serious flaws remain.

The law of prior consultation was developed to ensure discussions with indigenous people ahead of any natural resource development. Crucially, the law itself is only consultative and does not give people a veto over any development projects.

Environmental impact assessments are now being approved by the state faster than ever. Workshops and public hearings for local people – in theory, part of the impact assessment process – often occur after the government has signed oil and gas agreements. Affected citizens are therefore the last to know about these developments.

Development still trumps everything else

The Amazon rainforests of Peru are still considered an untapped resource. The government’s aggressive pursuit of development is designed to change this at the expense of local, predominantly indigenous people who are still seen as obstacles to Peru’s ongoing development.

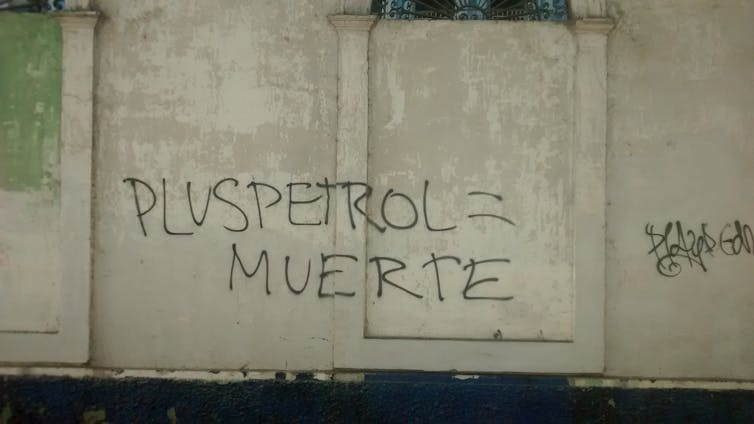

State-led consultation mechanisms and wider laws have been designed to ignore local peoples’ voices and attack environmental and human rights defenders. However, Peru’s high levels of social conflict surrounding mining and oil development projects are not only caused by ongoing environmental pollution issues and the overlapping of indigenous lands but also these consultation issues.

![]() This must change. The Peruvian state must listen to and respect the voices of its indigenous citizens.

This must change. The Peruvian state must listen to and respect the voices of its indigenous citizens.

Adrian Gonzalez, Lecturer, Royal Docks School of Business and Law, University of East London