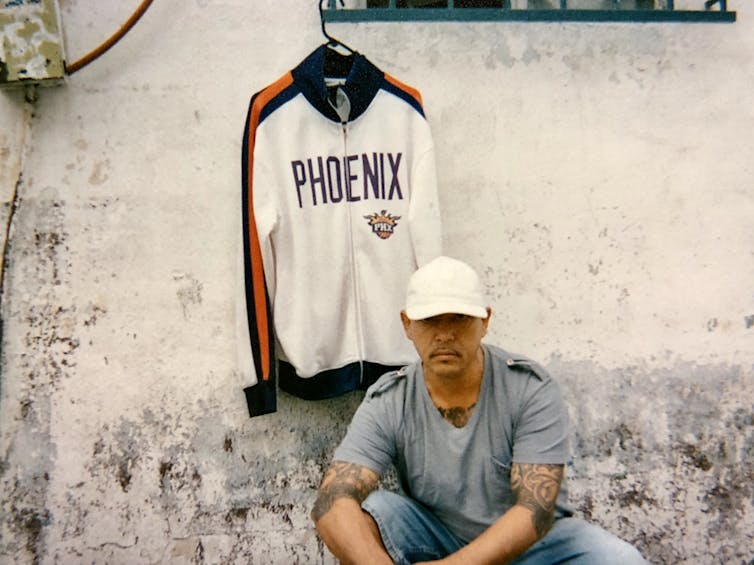

Ray was born in Mexico and moved to the United States with family members at age 10.

He told me in an interview in 2014, “I’m just a regular American like everyone else.” In middle school, Ray (a pseudonym to protect his identity) learned the Declaration of Independence and memorized all the presidents in order. His first job was replastering swimming pools in Phoenix, Arizona. Ray had a son, who was accepted to officer candidate school to attempt to earn the title of U.S. Marine.

After 29 years in the United States – attending school, working and raising a family – Ray was deported to Mexico.

As an anthropologist, I set out to understand how people like Ray become socially entwined in U.S. communities. I spent 18 months researching and living with deported adults in northern Mexico. I interviewed 56 deported adults who had arrived to the United States before age 13, years or even decades ago.

In English, marked by East Coast pluck, Southern lilt or Southwest flatness, they told me of the ties that bind them to their U.S. home communities. Their experiences raise important questions about the human costs of deportation that Washington lawmakers must consider as they debate immigration policy – particularly as it affects so-called Dreamers, noncitizens who have lived most of their lives in the United States.

Belonging and alienation

The people I interviewed articulated a deep sense of national belonging in the United States. Alfonso (pseudonym) was deported in 2013 after living for 43 years in Tucson, Arizona, since the age of 2. He told me, “The U.S. is everything for me. It’s everything I feel, everything I’ve ever done. It’s who I am. You grow up up there and that’s your life.”

They also spoke of lives that, before deportation, had been enmeshed in the everyday activities, shared understandings, social networks, ways of communicating and values of their local communities. Divorced from home, deportees often felt incomplete, shut out or shut down.

Paco (pseudonym) was born in Mexico in 1971, taken to Phoenix, Arizona, with family at 6 months old, and deported in 2013. He said, “It’s the little things that matter, you know: birthday parties, a quinceñera, graduations. Things happen up there and it’s just once, and you don’t get that time back.”

Deportees also experience wrenching social, psychological and economic stress and alienation after expulsion. They enter unfamiliar worlds when released from U.S. government custody, into northern Mexico border cities.

Paco expressed his disorientation in Mexico: “For me it’s like they dropped me off in Africa … In a place I don’t know, where I have nothing. I don’t know nobody [and it’s] not my home. I have no ties to nobody.”

After deportation, life’s more meaningful projects became daunting – turning a living space into a home, determining a vocation, attending school, connecting deeply with others, or imagining a future. Dustin (pseudonym), a 38-year-old deportee put it simply: “I’ve had enough with this down here. I just can’t do it. It’s just not like up there.”

To be sure, a mix of family support, academic or job skills, hard work, ingenuity and sheer grit, allowed some returnees to reconfigure their lives. In rare cases, some described achieving fulfillment and happiness. But they represent a narrow minority.

Most speak of “getting by” or “making it.” Rabbit (pseudonym), a 22-year-old deportee said, “Depression hit me pretty hard.” Rabbit describes feelings of dispossession and dejection and an inability to live a “normal life.” In characterizing the unrelenting pressure his feels, he said that he “lived in some of the hardest places [in Phoenix], and they didn’t get me. It’s just, Mexico’s got a grip on me now, and won’t let go.”

Fixing immigration policy

The Trump administration’s announcement on Sept. 5, 2017 that it was rescinding Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals consigned to Congress the responsibility of action on immigration legislation. Most of those I interviewed were given a lifetime ban from legally reentering the United States. They have little hope for returning home. But since DACA’s cancellation, DACA recipients still in the United States risk losing their protection from deportation. Deportees’ sense of belonging in the United States helps illuminate the potential ramifications of legislative inaction.

![]() Lawmakers, citizen and media discourse often focus immigration debates on noncitizens’ potential economic and social benefits to the United States. Nevertheless, the U.S. government also claims to ground policy decisions in principles of basic human well-being. In finding a way forward, legislators should consider the experiences of the untold deportees who, like Ray, have had their lives disrupted by dislocation from home.

Lawmakers, citizen and media discourse often focus immigration debates on noncitizens’ potential economic and social benefits to the United States. Nevertheless, the U.S. government also claims to ground policy decisions in principles of basic human well-being. In finding a way forward, legislators should consider the experiences of the untold deportees who, like Ray, have had their lives disrupted by dislocation from home.

Tobin Hansen, Ph.D. candidate in anthropology, University of Oregon