In the last few weeks, hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Katia have cut paths of destruction in the Caribbean, Mexico and the U.S.

In the last few weeks, hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Katia have cut paths of destruction in the Caribbean, Mexico and the U.S.

While recovery and reconstruction will be an immense effort in Houston and Miami, it will likely be slower in poorer and smaller countries outside the U.S. There, many people suffering from the aftermath of these storms may eventually choose to move elsewhere. How much new immigration can the U.S. expect in response to what may be the most destructive hurricane season the Americas has ever seen?

We come to this question having worked for more than a decade on how international migration benefits migrants’ countries of origin. For example, households back home benefit from monetary remittances sent by migrants, which fund small businesses and schooling and reduce child labor. Migrants also send remittances to help families cope with bad weather, such as droughts and hurricanes.

In new research, we turn to a related question: When people are hit by natural disasters, is international migration one way in which they cope with the aftermath? The answer isn’t obvious, but our data suggest that they do, under certain circumstances.

Understanding how immigration responds to major events in other countries helps policymakers understand the consequences of immigration policy. Immigration policies affect whether new migration can happen in response to a disaster overseas, and whether the migration happens via legal or undocumented channels.

How we approached the question

We focused on migration to the U.S., the world’s largest international migration destination.

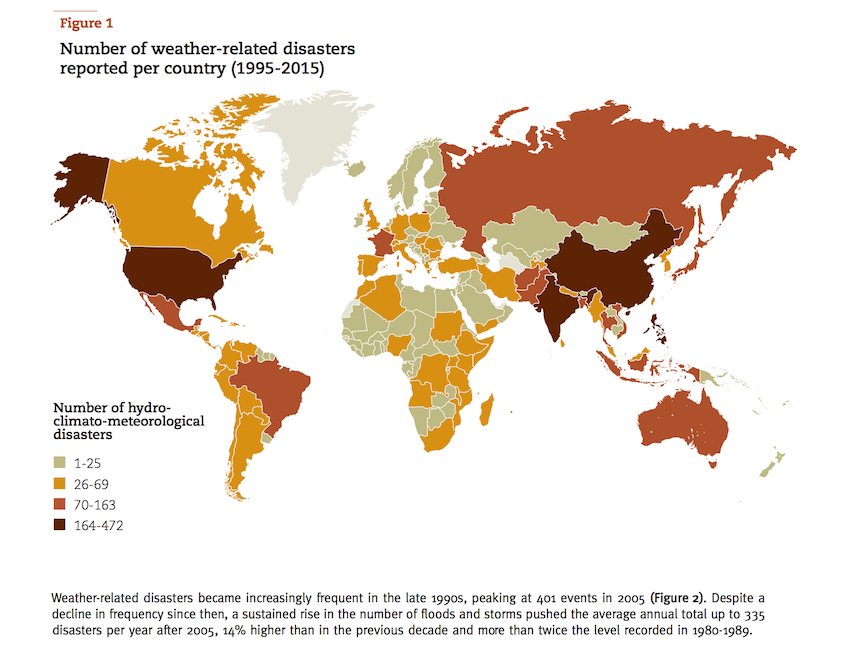

First, we evaluated the severity of a hurricane in a given country during a given year using a hurricane index we constructed. Hurricanes and related meteorological events such as flooding are among the most damaging types of disasters, accounting for roughly 40 percent of deaths and 38 percent of monetary damages caused by all natural disasters in the last two decades. What’s more, with climate change, hurricanes have been becoming stronger over the last few decades. Our hurricane index uses satellite data to estimate a country’s exposure to hurricanes, rather than relying on more subjective reports from governments or the media.

Then, we analyzed restricted-access U.S. Census data – which are accessible only to researchers with security clearance for reasons of confidentiality – from 159 countries over a quarter-century (1980-2004). We used these data to determine whether the U.S. saw a bump in the rate of immigration in years following large storms in other countries. We also analyzed official U.S. immigration data on new legal entries into the United States, such as whether immigrants entered the country on tourist or business visas, or with legal permanent resident status or “green cards.”

What we found

We found that when hurricanes hit other countries, the U.S. sees a bump in new immigration. Strikingly, the biggest spikes in migration rates are from countries from which larger shares of their populace had previously migrated to the U.S.

To figure out how people were getting to the U.S. in the wake of hurricanes, we probed the official U.S. immigration data. We found that hurricanes cause increases in the number of new green cards that are issued. In addition, there are even greater increases in entries to the U.S. in nonimmigrant categories – primarily tourist and business visas.

What’s going on here?

In the wake of hurricanes, networks of migrants living in the U.S. are helping ease the way for new migrants. Prior migrants are taking advantage of U.S. immigration policies that facilitate family reunification, which allow U.S. citizens and permanent residents to get green cards for relatives.

Aside from sponsoring relatives for green cards, networks of prior migrants may also be providing other types of assistance. As is often the case, they can help with housing and jobs, information about settling in a new country and culture, monetary support and psychological support. Prior migrants may also help new migrants figure out how to get tourist or business visas to enter the U.S. in the first place.

People may come to the U.S. on these nonimmigrant visas either with intentions to stay temporarily to seek shelter from the storm or with intentions to settle permanently. Unfortunately, our data can’t reveal how frequently people who enter in response to hurricanes on nonimmigrant visas end up staying permanently and whether they do so via legal or undocumented means. The available DHS nonimmigrant data do not link each individual nonimmigrant entry to each subsequent individual nonimmigrant exit.

Hurricane Cesar brought heavy rains that have caused extensive flooding and landslides throughout Costa Rica.

Hurricane Cesar brought heavy rains that have caused extensive flooding and landslides throughout Costa Rica.

AP Photo/Kent Gilbert

Central America and the Caribbean is one region where hurricane-driven migration to the U.S. is particularly pronounced. It is frequently hit by hurricanes that cause severe damage. And there are many immigrants from the region in the U.S. So people affected by hurricanes there often have family members who can sponsor them to come to the U.S. or provide other assistance to ease migration.

For example, Hurricane Cesar hit Nicaragua in 1996. It caused food shortages, 42 deaths, US$50.5 million in damages and left 100,000 people homeless. The years 1996 and 1997 both saw a 50 percent increase in green card holders from Nicaragua, compared to 1995. A large share of these new immigrants were immediate relatives of U.S. citizens – parents, spouses and children.

In comparison, Tropical Cyclone 04B struck Bangladesh in 1988, killing 5,708 and destroying more than half of the country’s agricultural harvest. Yet, there was no substantial migratory response from Bangladesh to the U.S. in 1988 and 1989.

What explains the difference between the Nicaragua and Bangladesh cases? Bangladesh features one of the smallest U.S. migrant networks in our sample. By contrast, the Nicaraguan migrant network in the U.S. is relatively large, and so can be more helpful for home-country compatriots seeking to migrate to the U.S.

Broader implications

Our findings highlight a previously underemphasized consequence of U.S. immigration policy: It defines a select group of people worldwide who can seek safe haven in the U.S. in the wake of disasters in their home countries. To be specific, family members of U.S. citizens and permanent residents are relatively easily able to move to the U.S. to escape a disaster’s consequences. Others without such connections are not so lucky, and must find other means of coping with the aftermath.

![]() This is an increasingly important consideration in immigration policy, as scientists predict climate change will mean an increase in the severity of natural disasters.

This is an increasingly important consideration in immigration policy, as scientists predict climate change will mean an increase in the severity of natural disasters.

Dean Yang, Professor of Economics and Public Policy, University of Michigan and Parag Mahajan, PhD Candidate in Public Policy & Economics, University of Michigan

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.