It seems like every month brings news of another border wall going up.

Europe’s Baltic States, worried about invasive neighbors, are raising a fence along their eastern frontier. Meanwhile, in Asia, Chinese President Xi Jinping is calling for the building of an iron wall around the Xinjiang region.

In Latin America, Ecuador appears to have begun erecting concrete panels along the Peruvian state line. In Africa, a barrier between Somalia and Kenya, made of barbed wire, concrete and posts, is nearing completion.

This is a far cry from the illusion generated by the fall of the Berlin Wall — and by the utopian dream of a world without borders that emerged in the 1990s.

The Wall: a new status quo in international relations

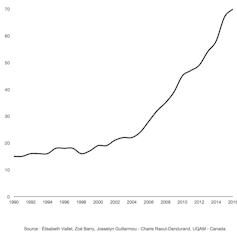

At the end of the Cold War there were just 15 walls delimiting national borders; today, with 70 of them in existence around the world, the wall has become the new standard for international relations.

With the proliferation of border walls and their normalization in the rhetoric of U.S. President Donald Trump, democracies have adopted the tactic as though it were a classic policy tool in foreign relations and defense.

And yet these rampant fortifications come at a hefty price, as much for the governments and international relations as for the local economies and populations affected. For those most vulnerable, for the middle class, for those pushed out by the walls (Saskia Sassen’s “expelled” peoples), the cost is exorbitant.

As symptoms of a rift in the world order, as manifestations of the failings of international cooperation, these barriers also come at a cost to those they shut out — the world’s “untouchables”.

The reality is that, despite being entrenched in international law, their freedom of movement is not as valuable as others’, each passport carrying its own set of rights.

The financial cost of border walls

First, we must consider the financial cost of border walls. Each one is a boon to the security and construction industries (many players from the former having adapted to changes in the post–Cold War defense market).

The experience in United States provides many examples of the cost of a massive border infrastructure. This typically involves not just a physical wall with stone foundations, posts, and even concrete panels, but also razor wire, cameras, heat sensors, movement detectors, drones and patrol personnel, dogs or robots, among other things.

That’s because a wall, by itself, doesn’t really work: it’s easy to scale it, put up a ladder, place ramps over the barrier to get a car across, fly drugs over it with drones, or use hydraulic fracturing to dig out narrow tunnels to circumvent it.

Customs Border Protection

In fact, in 2009, the U.S. Government Accountability Office placed the cost for building just a fence along California’s border at between $1 million Cdn and $6.4 million Cdn per kilometer. In harsher terrain jurisdictionally and geologically, such as the Texas state line, the building cost could be as much as $21 million a kilometer.

Maintaining it for 20 years will cost an estimated $8.5 billion; it is therefore a massive public infrastructure, akin to a giant highway, that eats away at a country’s public finances and, in turn, at overall disposable income (whether funding comes from public sources or in part from private sources).

So this financial burden is also an economic weight that drags down the country’s aggregate income as well as the local economy. The latter, often significantly affected by the slowing down and redefining of cross-border activity, legal or otherwise, is sometimes put on life support in the form of an influx of military or patrol personnel, construction crews and staff for related services (restaurants, hotels, and so on).

Walling our countries in: The human cost

Migrants near the border wall between Mexico and the United States.

Migrants near the border wall between Mexico and the United States.

qbac07/Flickr, CC BY-NC

There is also a human component to the economic cost. There is, in fact, a proven correlation between the fortification of borders and the number of people who die trying to cross them. In the United States, where local advocacy groups actively seek out and disclose this information, 6,000 deaths in the desert) along the border have been recorded in the last 16 years.

Since the tightening of European policies, the Mediterranean has become a “dead sea,” to paraphrase cartographer Nicolas Lambert, who maps tragedies befalling migrants in the region, where the number of deaths continues to climb despite a decline in the total number of crossing attempts.

In fact, to get across a fortified and tightly controlled border, the available routes are often far more treacherous, pose greater threats and require resorting to smugglers, who are sometimes linked to organized crime groups like the Mafia.

Violence is amplified when the border is militarized. First and foremost, because such militarization legitimizes the perception of the border zone as a theatre of operations, a war zone, where paramilitary groups feel justified to act, as in their deployments along the Hungarian border.

Secondly, by adding military personnel or army veterans to border patrol forces (they account for a third of such teams in the U.S.), the tactics come to match those used in war zones, bringing with them patent impunity and violence, as reported by authors Todd Miller, Reece Jones and others.

Lastly, by forcing clandestine border crossing to become even more hidden, by pushing migrants deeper underground, these measures reinforce the power of Mafia and organized crime groups, and increase the violent extortion or coercion of vulnerable migrants (through kidnappings and ransom demands, for example). From the borders of Southeast Asia to the Sahel Region, and from the corridors leading from Central America to the U.S. or from Turkey to continental Greece, it is the most vulnerable migrants who suffer the repercussions of the world’s border walls.

Thus, sexual assault has become a common event in women’s migratory journey, with 80 per cent of them being assaulted along their route to the United States; the NGOs they encounter along the way systematically dole out contraceptives.

Division as a political cost

Constructing walls also comes at a political price. Since putting up a wall is a one-sided act — the farthest thing from the bilateral reasoning behind drawing state lines — it induces a separation from the neighboring state, rather than fostering co-operation with it.

tgraham/Flickr, CC BY-NC

The rift created by the wall sends shock waves through other facets of the relationship between the nations. In the case of Trump’s wall, the cost of the split with Mexico is high, given this trade partner’s importance to the U.S. economy as well as to the other bordering states. Within the migratory channels that are increasingly popular with refugees, the neighboring states often serve as filters.

Erecting a wall at the border may influence not just how these other countries play their role as advanced border checkpoints, but also how they set their own defense and security policy, which can sometimes lead to a form of extroversion, that is, a kind of appropriation of the discourse of the walled State at the expense of the national interests of the other.

Canada is not immune to any of this, either. In fact, in response to the presidential transition team’s request for information on the borders in December 2016, U.S. Customs and Border Protection confirmed the need to fence off more than 640 kilometers of the country’s southern border, but also some of its northern border between Canada and Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Montana, Idaho and Washington.

Fundamentally flawed

On June 3, The Economist published an article on the need to build a wall at the border with Canada, mainly to prevent drug smuggling.

Hadrian’s Wall, built in northern England in the 2nd century AD.

Hadrian’s Wall, built in northern England in the 2nd century AD.

Alan Bloom/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

Yet no wall has ever succeeded in permanently eliminating contraband. Ramps, catapults, drones, tunnels, submarines, mules or even corrupt border guards can always undermine its effectiveness; or the traffic merely shifts elsewhere. A wall simply pushes us farther from getting to the heart of the matter, from addressing the root problem, from treating the illness and not just the symptoms.

![]() As border walls erode the potential for international cooperation and community, the world’s problems keep growing: food insecurity, ethnic conflicts, environmental crises, climate change, massive displacements of people. Many different problems bring nations to build walls, but we should recognize them as pointless facades that must, in the end, come tumbling down.

As border walls erode the potential for international cooperation and community, the world’s problems keep growing: food insecurity, ethnic conflicts, environmental crises, climate change, massive displacements of people. Many different problems bring nations to build walls, but we should recognize them as pointless facades that must, in the end, come tumbling down.

Elisabeth Vallet, Director – Center for Geopolitical Studies, Université du Québec à Montréal

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.