If the world is to transition to a climate-compatible future, much will turn on new innovations in clean energy and whether they can be deployed at a large scale. This is especially critical for emerging economies, which are developing their infrastructure and undergoing economic growth and urbanisation at an unprecedented scale and pace, yet still often lack the support for technological innovation found in wealthier countries.

Six of these emerging economies – Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico and South Africa – contributed more than 40% of the global CO₂ emissions in 2019. That’s 1.5 times the combined emissions from the US and Europe. Yet at the same time China, India, and Brazil were the first, fourth and sixth largest producers of renewable electricity. These three countries – the largest emerging economies – are now at a crucial juncture, faced with immense potential to become major innovators in the development of clean energy technology.

In a new paper we explored how fast-growing countries can not only develop their own sustainable systems but provide a source of learning and knowledge to influence global trends. We did this by investigating specific clean energy success stories in the three countries.

India’s remarkable transition to LEDs

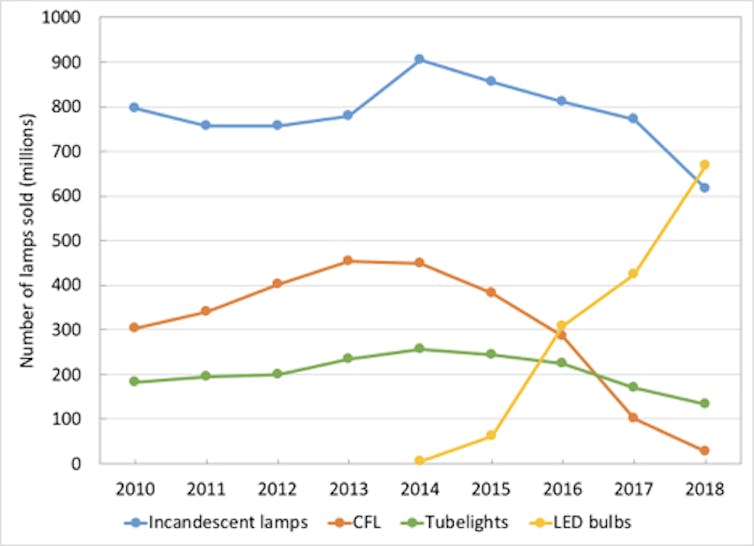

First is India’s 130-fold expansion of its market for light emitting diode (LED) bulbs in just five years. LED bulbs are more energy efficient and last much longer than incandescent bulbs, tube lights, and compact fluorescent bulbs. In India they are primarily being used for residential lighting and street lamps.

India’s LED transition is estimated to save more than 40 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity each year – roughly enough to power 37 million average Indian households or the whole of Denmark for one year. In three years, the country grew from a negligible share of the global LED market to about 10%.

Solar energy soars in China

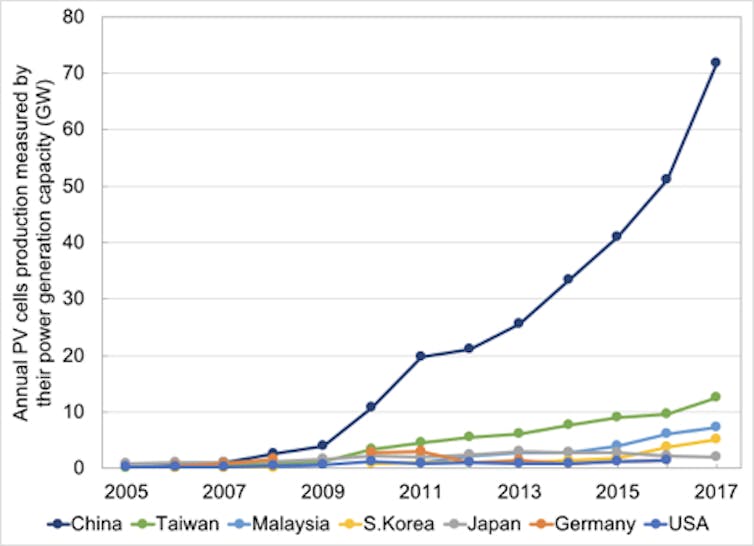

An equally remarkable transition occurred in China, which has become the top manufacturer and largest market of solar photovoltaic (PV) cells and modules, accounting for 69% of global production. In the past 40 years, solar panel costs have declined by more than 99%, driven recently by low-cost manufacturing in China.

Between 2014 and 2018, China added about 158 gigawatts of solar PV – about the same as the total power generation capacity of Brazil.

Khosla et al (Data: IEA-PVPS annual Trends Reports and National Survey Reports for China, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea and the US), Author provided

Biofuels in Brazil

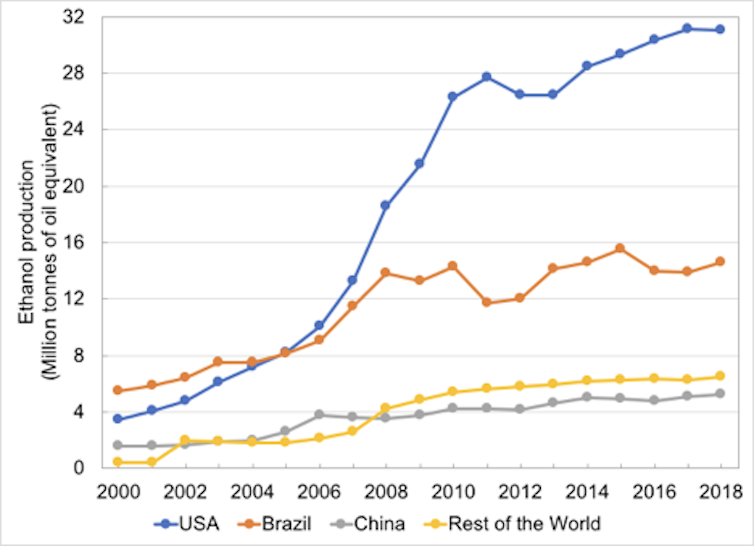

A third success story is that of Brazil’s long-term growth to become the largest producer, exporter and market for ethanol biofuel made from sugarcane.

Ethanol-run vehicles increased their share of Brazil’s new car sales from 30% in 1980 to 90% in 1985. After ethanol stagnated in the 1990s, biofuels were revived by the introduction of flex-fuel vehicles which use any mix of gasoline and ethanol. Their share increased from negligible in 2003 to 85% of new cars sold just five years later – and has remained constant since.

There are some environmental and socioeconomic impacts. These include deforestation for sugarcane plantations, soil erosion, air and water pollution, and the consolidation of land ownership among large ethanol producers. But when you look at the full lifecycle of sugarcane ethanol fuel, from crop to car, its greenhouse gas emissions are lower than those from gasoline or corn ethanol.

Three lessons for the rest of the world

Based on these unexpected clean-energy transitions, we have identified three insights relevant across emerging economies.

1. Public sector enterprises are crucial

In all three cases businesses with significant equity owned by governments played a crucial role. In India, a joint venture of four public-sector utilities called EESL bought energy-efficient LED bulbs in bulk, reduced prices using competitive bidding, ran national marketing campaigns, and sold the bulbs to customers through new distribution channels.

In China, public sector enterprises provided venture capital investments and loans that enabled rapid expansion of private sector solar startups. In Brazil, the leading public oil company bridged the gap between ethanol production and consumer point-of-purchase by buying ethanol from mills, providing storage and transport, and distributing fuel through the country’s largest network of fuel pumps.

2. Domestic choices in a global economy

Second is the need to reinforce complementary links between the global economy and domestic technology choices. For example, India was able to accelerate its LED market because its bulk procurement and bulb distribution policies complemented access to China’s large scale low-cost LED manufacturing. Equally, China’s early domestic support for export-oriented hi-tech manufacturing complemented the growing demand for solar cells in Germany.

3. R&D that unites academia and industry

Finally, engagement between industry and universities and public sector research institutions is essential. For example, Brazil could develop the technology to make ethanol compete on cost with gasoline only because of strong links between public sector research institutes and industry, including the government-funded “Sugarcane Genome Project”.

Our analysis shows that it is possible for emerging economies to begin from a technologically and economically disadvantaged position and yet successfully accelerate the transition to clean energy technologies. These lessons provide good news, since success or failure in this endeavour will have long-term energy and climate consequences for all.![]()

Radhika Khosla, Senior Researcher at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford, University of Oxford; Ajinkya Shrish Kamat, Postdoctoral Associate, Institute for Data, Systems, and Society, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Venkatesh Narayanamurti, Benjamin Peirce Professor of Technology and Public Policy, Harvard University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.